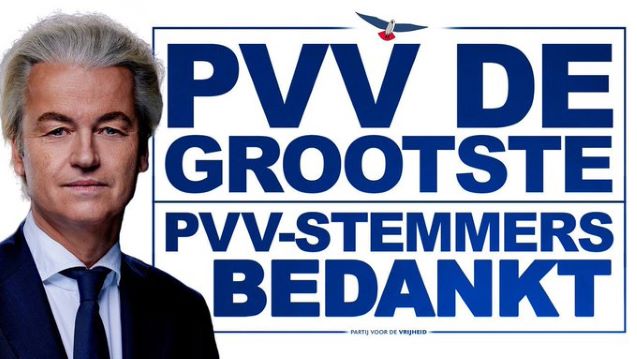

Veteran anti-Islam populist leader Geert Wilders has won a dramatic victory in the Dutch general election, with almost all votes counted.

After 25 years in parliament, his Freedom party (PVV) is set to win 37 seats, well ahead of his nearest rival, a left-wing alliance.

“The PVV can no longer be ignored,” he said. “We will govern.”

His win has shaken Dutch politics and it will send a shock across Europe too.

But to fulfil his pledge to be “prime minister for everyone”, he will have to persuade other parties to join him in a coalition. His target is 76 seats in the 150-seat parliament.

At a party meeting on Thursday, Mr Wilders, 60, was cheered and toasted by party members in a room crammed with TV cameras.

He told the BBC that “of course” he was willing to negotiate and compromise with other parties to become prime minister.

The PVV leader won after harnessing widespread frustration about migration, promising “borders closed” and putting on hold his promise to ban the Koran.

He was in combative mood in his victory speech: “We want to govern and… we will govern. [The seat numbers are] an enormous compliment but an enormous responsibility too.”

Before the vote, the three other big parties ruled out taking part in a Wilders-led government because of his far-right policies. But that might change because of the scale of his victory.

The left-wing alliance under ex-EU commissioner Frans Timmermans has come a distant second with 25 seats, according to a forecast based on 94% of the vote.

He made clear he would have nothing to do with a Wilders-led government, promising to defend Dutch democracy and rule of law. “We won’t let anyone in the Netherlands go. In the Netherlands everyone is equal,” he told supporters.

That leaves third-placed centre-right liberal VVD under new leader Dilan Yesilgöz, and a brand new party formed by whistleblower MP Pieter Omtzigt in fourth – both have congratulated him on the result.

Although Ms Yesilgöz doubts Mr Wilders will be able to find the numbers he needs, she says it is up to her party colleagues to decide how to respond. Before the election she insisted she would not serve in a Wilders-led cabinet, but did not rule out working with him if she won.

Mr Omtzigt said initially his New Social Contract party would not work with Mr Wilders, but now says they are “available to turn this trust [of voters] into action”.

A Wilders victory will send shockwaves around Europe, as the Netherlands is one of the founding members of what became the European Union.

Nationalist and far-right leaders around Europe praised his achievement. In France, Marine Le Pen said it “confirms the growing attachment to the defence of national identities”.

Mr Wilders wants to hold a “Nexit” referendum to leave the EU, although he recognises there is no national mood to do so. He will have a hard time convincing any major prospective coalition partner to sign up to that.

He tempered his anti-Islam rhetoric in the run-up to the vote, saying there were more pressing issues at the moment and he was prepared to “put in the fridge” his policies on banning mosques and Islamic schools.

The strategy was a success, more than doubling his PVV party’s numbers in parliament.

During the campaign Mr Wilders took advantage of widespread dissatisfaction with the previous government, which collapsed in a disagreement over asylum rules.

For political scientist Martin Rosema from the University of Twente, it was one of several gifts that had been handed to Mr Wilders on a plate in a matter of months. Another was that the centre-right liberal leader had opened the door to working with him in coalition.

“We know, also from international precedent, that radical right-wing parties fare worse when they’re excluded,” he said.

Migration became one of the main themes, and Mr Wilders made clear on Wednesday he intended to tackle a “tsunami of asylum and immigration”.

Last year net migration into the Netherlands more than doubled beyond 220,000, partly because of refugees fleeing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But the issue has been aggravated by a shortage of some 390,000 homes.

At the Hague headquarters of Ms Yesilgöz’s VVD, supporters had been preparing to raise their glasses at the prospect of the Netherlands’ first female prime minister.

But there was a collective gasp of disbelief when the exit polls flashed up on the screens and they huddled over their phones trying to understand what went wrong.

Ms Yesilgöz took over as centre-right leader when the country’s longest-serving prime minister, Mark Rutte, bowed out of politics in July. She came to the Netherlands as a seven-year-old refugee from Turkey but has adopted a hard line on immigration.

Some politicians and Muslim figures have accused her of opening the door to the far right by refusing to rule out working with Geert Wilders.

Ms Yesilgöz, 46, had tried to distance herself from the Rutte government in which she was justice minister, but ultimately she was unable to live up to the opinion polls.

Right up to the eve of the election, almost half of the electorate were being described as floating voters. Many of those may well have decided not to back her.

A measure of Mr Wilders’ success in winning over voters came from one Muslim voter in The Hague who said: “If he wasn’t so opposed to Muslims, I’d be interested in him.”

Hours before the vote, Mr Wilders was buoyant about his chances, telling the BBC. “I think it’s the first time ever in Holland that in one week we gained 10 seats in the polls.”

He was realistic about the uphill task he faced in forming a government led by him, but he said he was a positive person and victory would make it “difficult for the other parties to ignore us”.__Courtesy bbc.com