When you type ‘Sikhism’ on Google, some of the popular searches include “What is the highest caste in Sikhism?”, “What is a chamar Sikh caste?” Sikhism was envisioned as an order free from the anomalies created due to social structures that sanctions a false sense of entitlement to some and a life of indignity to others. With separate places of worship, cemeteries and other socio-cultural institutions, the reality is far from the vision with which it was formed.

“Malwa region reports the majority of caste discrimination cases where Bant Singh’s case made it to headlines because of the cruelty and severity of the crime against him. Some goons from upper caste group tortured him because of his involvement in political and social activities regarding the upliftment of Dalits. In this region, Dalits face social ostracism and are not given work in the village if they try to assert themselves. So if one wants to understand the situation of Dalits in Punjab, one cannot ignore these regional disparities and uneven social make-up,” says Ravinder Kaur, Assistant Professor of English at Panjab University in Chandigarh. Bant Singh’s case is a grim reminder of caste-related violence in Punjab where he was brutally assaulted because he was raising his voice against the rape of his minor daughter. Both his legs and hands were chopped off.

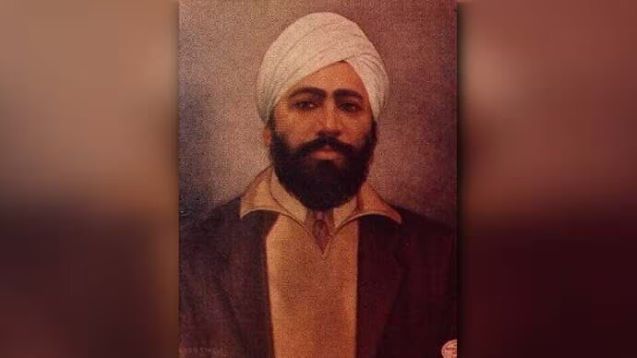

As we remember Shaheed Udham Singh on his death anniversary today, we must raise some questions that might be unpalatable to a large section of people who have benefited from these oppressive structures of power and privileges. At almost 32 per cent, Dalits form a considerable part of the population in Punjab. The sheer amount of discrimination faced by a Dalit in everyday interaction in Punjab must be a matter of research and scholarship. Anyone from Punjab can tell you about the large-scale prevalence of caste gurudwaras in the state. The rise of Manyawar Kanshiram as one of the tallest Dalit leaders of independent India is a testimony to the predominant social tensions in the region.

In the course of my readings on Udham Singh’s life, I came across an article where the picture of Shaheed Chandrashekhar Azad was used as a representational image for Shaheed Udham Singh. It has been there for the past year. Those who filed the article are not to be blamed for this. But mistakes — conscious or unwilling like this — are indicative of the seriousness that the media attaches to the icons and issues of the subaltern segment of our society.

The life and struggle of Udham Singh must be read, analysed and commemorated. Udham Singh was a child raised in an orphanage who was volunteering at the protest meeting on the day that brought infamy to our history. The fate of that child was sealed on that very day. Udham Singh decided to avenge the killings.

As an active member of the Ghadar party, he first started as a labourer in Africa and then reached London, after travelling through many European countries and spreading the message of independence. He was able to kill Michael O’ Dwyer at the Caxton hall in London on March 13, 1940. After a brief trial, he was hanged on this day 80 years ago.

Udham Singh’s contribution to the struggle for independence is in no way less than that of other contemporary freedom fighters. Why did he not receive the same attention by the writers of history?

The chroniclers of history, in their blind adoration for one family of politicians, consciously buried the contributions of such unsung heroes. Look at the numbers of articles on Rani Jhalkari Bai, Uda Devi Pasi, Matadin Bhangi and the number of other Dalits who laid their lives for the sake of the nation. With the New Education Policy, I am hopeful that the new generation of historians would be more generous to the Dalit heroes — men and women — who sacrificed everything in the pursuit of collective liberation.

Today, when a section of our intelligentsia is out to comment on the nationalism of Dalits, Udham Singh’s life is a strong testament to the contrary. Dalits, throughout history, have been deeply patriotic and have never shied away from making the supreme sacrifice for the nation and the society, if the situation demanded. The so-called Dalit intellectuals must realise this in perpetuating the divisive narrative, and the present-generation Dalits like myself will continue to take immense pride in the role of Dalit history in the nation-building.__Daily O